Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF), a diagnosis not so Familial, not Mediterranean, but with Fever

AI Generated

Objectives

Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF) is a disease included in the group of autoinflammatory diseases , with a specific constellation of signs and symptoms. While the genetic and clinical picture is well known, people affected by this process suffered, quite often, a diagnostic delay, not just days or months, but several years. We will expose here the possible causes associated with this diagnostic delay, describing two clinical cases.

Background

FMF has been described initially in subjects of the Eastern Mediterranean ascendent (1), but it is considered now, as a worldwide clinical entity. The name “familial” wants to enhance the genetic origin of the disease to differentiate it from other syndromes with fever associated with an infection or an immunologic condition. Inheritance follows an autosomal recessive pattern, with a mutation in the MEFV gene (2), but the complete genetic landscape is not totally understood, because some patients are heterozygote for the mutation and several other mutations are also associated with the disease (3).

The diagnostic criteria are well established in the medical literature (Tell-Hashomer criteria, Livneh criteria, Printo(4). Fever, serositis, are almost universally present, and, quite often, these symptoms can be misleading as a viral infection, giving rise to a delay in diagnosis. Studies in population of eastern Mediterranean origin have shown some variables associated with a diagnostic delay (5).

We report here two clinical cases, one with a clinical diagnosis and other with a genetic confirmation,

with the intention of describing a clinical pattern, and to explore possible diagnostic biases involved in the diagnostic delay.

Case 1

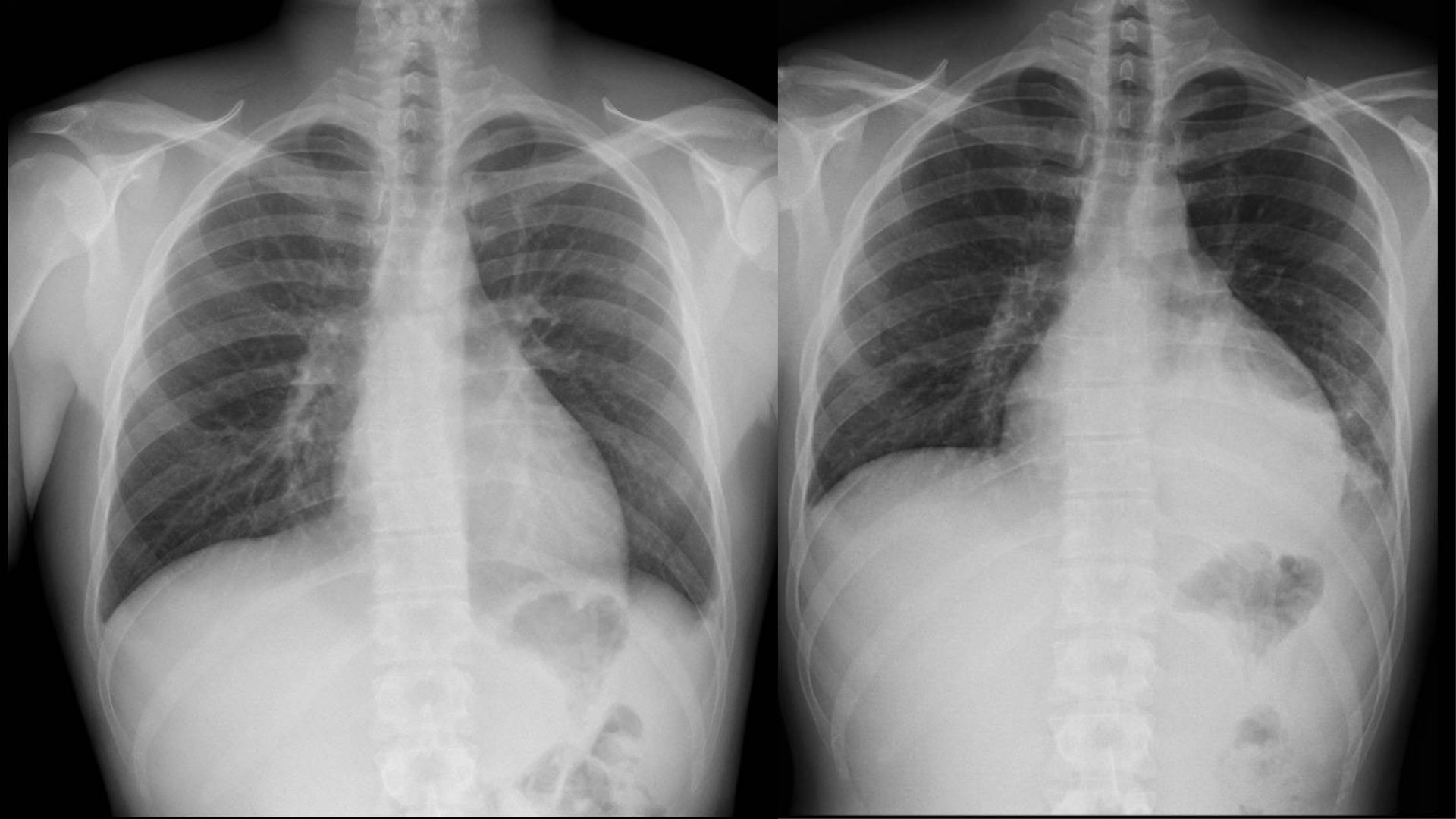

A 22-year-old man started during the Covid pandemia with an acute fever, chills, shortness of breath and a central thoracic pain. Physical examination showed a lack of ventilation in the basal right lung and tenderness in the right upper quadrant. Blood and urine cultures, and an exhaustive laboratory work for bacteria and viruses, were negative. The radiology and a cardiac sonogram showed a mild left pleural effusion and pericardia fluid. No cancer cells were detected in the analysis of the pleural effusion. There was a significant increase in the level of acute phase reactants like ferritin, over five times the normal value. The patient started an empiric treatment with a non-steroidal antiinflammatory drug, oxygen, a low dose of steroid, and paracetamol, with a clear general improvement in his clinical condition after the fourth day.

The patient reported three similar episodes in the previous year, usually during times of stress. He decided not to do a genetic test.

In Figure 1. we show the dramatic changes in the size of the cardiac silhouette between a period of two weeks.

Case 2

A 19-year-old woman started with an acute anterior thoracic pain, without fever, with a normal pulmonary radiology. She was treated with analgesic and the pain disappeared in the fourth day. She had a previous history of autoimmune thyroiditis, and recurrent pharyngoamigdalitis. One year and a half later, she started again with an acute centrothoracic pain, a very high fever (39 ª C) , myalgia and artralgias, with ST-changes in the electrocardiogram, receiving a diagnosis of myopericarditis. The patient had four more episodes with fever and thoracic pain during a period of four years. A genetic test confirmed the diagnosis of FMF.

Analysis

FMF is a disease prone to a diagnostic delay for several reasons. One important aspect is the presence of fever as a key data, a symptom shared with many other diseases, infections or inflammatory. Also, FMF is a disease with a low prevalence, and the consideration like a “Mediterranean” entity can be an important bias-inducer because, nowadays we know that there are not geographical boundaries for this condition. The consideration as a “familial” disease can be also a factor that could be associated with a wrong clinical judgment, because the patterns of inheritance is not totally unraveled, and the prediction of what a member of the family will show the whole clinical picture is not possible.

Conclusion

FMF must be taken into account as a possible diagnosis when a person, usually starting at a young age, suffered episodic fever without the detection of an infectious agent, mostly when pericarditis or mild ascites, abdominal pain and arthralgia are present and accompanied with an important general deterioration. A complete summary of previous medical visits to the Pediatrician, General Practitioner or Emergency Department , together with a complete family history, can help to achieve a diagnosis without a major delay.

Bibliography

1 Ozen F. Familial Mediterranean Fever. Rheumatol Int 2006; 26: 489-496

2 French FMF Consortium. A candidate gene for familial Mediterranean fever. Nat Genet 1997; 17-25

3 Lancieri, M; et al. An Update on Familial Mediterranean Fever. Int J Mol Sci 2023; 24,9584

4 Gattorno M, Hofer M, Federici S, et al. Eurofever Registry and the Paediatric Rheumatology

International Trials Organisation (PRINTO) Classification criteria for autoinflammatory recurrent fevers.Ann Rheum Dis 2019; 78: 1025-1032

Author: Dr. Lorenzo Alonso Carrión

FORO OSLER